To those who believe aviation is dying: Take your head out of the sand and look around, you're looking at the wrong aviation! Take a look at sport aviation, specifically that part of it represented by the so-called "homebuilt" or amateur-built airplane. It is enjoying explosive growth.

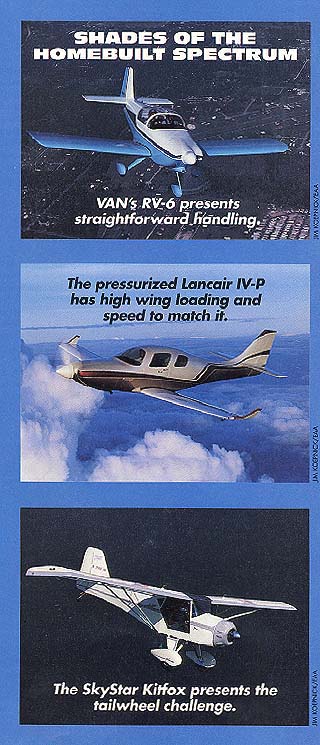

At least three times a day a new homebuilt aircraft of some kind takes to the air. They range from 50 mph ultralights and very light aircraft to 350 mph composite super birds that can smoke past a King Air with ease.

Aviation isn't dying...it's just changing its feathers. In the process it is generating an entirely new need for an entirely new type of training. .

The growth in the homebuilt area hasn't been without its problems, chief of which is that nearly 25% of all homebuilt accidents happen within the first five flights. Of that number, the vast majority occur because the pilot is flying an airplane for which he isn't qualified. In this case being qualified has absolutely nothing to do with what we usually think of as "qualifications" in traditional aviation.

Having made the requisite takeoffs and landings in the past 90 days does nothing to prepare a pilot to fly most homebuilt aircraft. Ditto for three hours of dual with his favorite CFI in the club's C-172. Depending on the homebuilt to be flown, 10,000 hours and an ATP don't even rate as qualifications.

Being qualified in the case of a homebuilt means at least three points, currency, proficiency and the adaptability of the pilot (and the CFI) have to be honed to match the homebuilt to be flown. Nothing else matters.

The reason traditional qualifications don't mean much in this situation is because homebuilt's are a different breed of cat. Because of the great variation within the breed, saying they are different is just about the only generality that can be made about them. Some of them are only slightly different, others are wildly different, but none of them is a C-152, although a few of them do have a little Cherokee running through their veins.

It is this "difference" and the pilot's ability to deal with that difference that decides whether he or she is going to have problems during those critical first few flights.

When we say a homebuilt is different, what are we talking about and how does a pilot or CFI prepare for it?

Homebuilt Differences

Every airplane of any kind, homebuilt or otherwise, flies differently than the next but in traditional aviation they all fall within certain parameters. The limitations imposed by certification have made the entire generation breed similar enough that they are fairly predictible, one make to another. Cessna to Beech to Mooney, etc, there are few real surprises. The consistency of production-line assembly has done that for each specific make and model. All C-172s fly pretty much the same, ditto Cherokees, etc. Going from one gen-av airplane to the next, although there will be small differences, you generally have a fair idea of what to expect.

In the homebuilt category none

of the above is true. For one thing just the fact that they are

homebuilt means everyone of them carries a little of the builder

with them, so each is as individualistic as the builder's thumb

print. The empty weight is the biggest culprit in changing the

characteristics within a given type (i.e. RV-6, Kit Fox, etc.).

Builder's often get carried away with upholstery or gadgetry and

an extra 100 pounds creeps into the airframe. Because the aircraft

are smaller than traditional birds that weight translates into

noticeably higher stall speeds, longer takeoff, faster rate of

descent, etc.. So, even within a given make and model, there are

differences.

In the homebuilt category none

of the above is true. For one thing just the fact that they are

homebuilt means everyone of them carries a little of the builder

with them, so each is as individualistic as the builder's thumb

print. The empty weight is the biggest culprit in changing the

characteristics within a given type (i.e. RV-6, Kit Fox, etc.).

Builder's often get carried away with upholstery or gadgetry and

an extra 100 pounds creeps into the airframe. Because the aircraft

are smaller than traditional birds that weight translates into

noticeably higher stall speeds, longer takeoff, faster rate of

descent, etc.. So, even within a given make and model, there are

differences.

And then there is the craftsmanship difference. One Skybolt may have slick quick ailerons and roll-out straight as a die on landing while the next may feel like a truck and dart around the runway like a ferret on speed. One may cruise at 135 mph and the next at 110 mph. The airplane's characteristics are greatly affected by the craftsman's ability to build to the plans and keep everything straight.

Homebuilts are also prone to system or operational quirks which were built in by the builder. Maybe the canopy latch has to be pushed a certain way to stay closed or the fuel system vents demand the throttle be handled gingerly at low speeds.

And then there is the wild diversity of models, from Lancair IV to Kit Fox and beyond. Each of the airplanes has its own personality and the pilot and CFI have to understand that personality and be able to acclimate to it.

In general a pilot new to homebuilts (remember this is the most dangerous of all aviation terms, a generality) will find they aren't as stable as Wichita Spam Cans, especially in approach, and they take more work to hold proper speeds in the pattern. In general the aircraft will do everything faster and more quickly than their factory-built cousins. They climb faster (usually) and fall out of the air faster power-off (always). In most designs, the homebuilt responds much more quickly to control inputs, so the pilot has to be aware of what he is asking the airplane to do, because it will do it immediately. If he pushes the stick forward, the nose will drop immediately, and vice versa, which often leads to a PIO in pitch on the first takeoff.

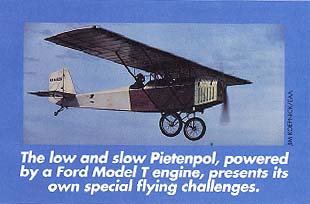

There are some homebuilts in which just the opposite of the

above is true. The old Pietenpol, for instance, redefines drag

and lazy control response as do most aircraft close to the ultralight

category. In aircraft like this, staying ahead of the aircraft

isn't the problem, but getting used to their high amount of drag

the way in which they react to the outside elements takes time.

Basically what we're saying here, in case  you haven't figured it out, is

that transitioning into a homebuilt airplane takes training that

is very specific to that airplane. But, where do you get that

training?

you haven't figured it out, is

that transitioning into a homebuilt airplane takes training that

is very specific to that airplane. But, where do you get that

training?

Homebuilt Training

The first step for anybody preparing to fly any kind of a homebuilt aircraft is to call EAA headquarters (414-426-4800) and ask for Earl Lawrence or anyone in the Flight Advisor program office. The Flight Advisor is a new EAA program in which pilots experienced in specific types of sport aircraft and especially homebuilts are designated as experts in that particular type and their expertise is made available to wannabee homebuilt pilots. In effect, the EAA has a designated corps of pilots willing to be a mentor to those needing help in transitioning. The Flight Advisor won't actually fly with you, but they will explain what to expect, analyze your airplane to ascertain how it compares to others of its type and most important, he'll analyze your experience, currency and proficiency to help you see how it matches what the airplane needs.

What the Flight Advisor does is guide the new pilot through a formalized self-evaluation of his background and capabilities so the pilot sees where there is an obvious mismatch. If all his current experience is in C-152s and he's getting ready to launch in a Glasair III, he'll see why no amount of C-152 time will prepare him for the high speeds and even higher wing loadings.

The obvious next step in that kind of situation is training. If the Flight Advisor is a CFI or is willing to do the check-out, he may remove his Flight Advisor hat (he can't fly with you as an EAA Flight Advisor) and strap in. If not, he'll suggest a training curriculum and help you evaluate what kind of instructor you need and what kind of qualifications that instructor must have.

Re-read that last sentence. Just because insurance companies have a love affair with the title "CFI" and think that makes them/us omnipotent, it doesn't. Just because a pilot has 15,000 hours instructing doesn't mean he knows enough about the homebuilt in question to be able to give you meaningful instruction for it.

Most of us instructors spend our time droning around the patch in a small number of specific aircraft types, i.e. your traditional Piper/Cessna trainer. Unless we have a reasonable amount of flight time in the homebuilt in question, A) we can't accurately modify our instruction technique within the traditional trainer environment to give the pilot enough knowledge to make him safe in the new airplane and B) we aren't safe enough ourselves to give dual to the pilot in his own homebuilt airplane.

Stay away from the instructor who says, "...nah, I've never actually flown one, but I hear they're no big deal..." 200 feet on short final with an inexperienced pilot at the controls is a bad time for the instructor to find out how wrong he was.

Number one rule of transitioning into a homebuilt: Don't take dual in that airplane from anyone who has less than 25-50 hours in them and preferably more.

Cross Training

In most situations it will be very difficult to find an instructor to actually give you dual in your homebuilt airplane. Usually you'll have to do the next best thing and seek out instruction that will prepare you to make that transition yourself. This is obviously true for all single-place homebuilts.

It's likely that most pilots will have to get training which is conducted in a Spam Can trainer and only approximates what they will see in their homebuilt. In that kind of "surrogate training" it is important the instructor or check-out pilot be familiar with the homebuilt so he can alter the way he instructs and the way he flies the Spam Can. To approximate higher approach speeds, he may make landings faster and without flap. He may use more or less power or may approximate a draggy airframe by flying the entire pattern with full flaps.

Assuming you can't take dual instruction in your own homebuilt (after its flight test period is over) the best approach is to find a knowledgeable instructor and an "equivalent airplane" to use as a trainer. An equivalent airplane is a more-or-less normal general aviation bird that has some of the same characteristics of the homebuilt so it builds a lot of the right instincts into the pilot.

For a majority of the most popular kit planes (Lancair, Glasair, RV, etc.) one of the early two place Yankees, especially an AA-1A or -1B, would be as close as you could come. It has a swiveling nose wheel, fast acting controls, glides at a steep angle and generally feels like a homebuilt. To build retract experience, a Bonanza in no-flap landings would also be a good choice.

For tailwheel experience, a pilot could begin climbing the ladder almost anywhere (Champ, Cub, etc.) but how many rungs up the ladder he or she has to go depends on the airplane to be flown. The most-available tailwheel trainer is the Citabria which is a good choice, but most often it should be flown from the back seat to get used to being blind. If the homebuilt is something a little hotter with quicker acting controls, a Pitts S-2A or S-2B is the ticket.

Proficiency and Adaptability

Knowing which airplane to select for training and how much

training should be done requires doing the self-analysis which

is at the core of the EAA's Flight Advisor program. The analysis

is aimed at several factors including:

· Experience. What have you flown which is similar to the

homebuilt in the following areas: wing loading, power loading,

control response, stall speed.

· Currency. How many landings, not hours, have you actually

logged in the last six months? How about the last year?

· Proficiency. Ignoring the hours and landings in the log

book, the real question is how proficiency are you? How well do

you actually fly?

This last point, proficiency, is a hard one to quantify. Also, when transitioning to a homebuilt which undoubtedly has some unfamiliar characteristics, there is the additional question of adaptability...how fast do you adapt to a new environment and handling package? It's really easy for someone who has only flown a few different types to find themselves mentally overloaded by the newness of everything so adaptability is a critical factor.

One way to test both the basic proficiency and adaptability is to book a CFI and an airplane and go for a proficiency ride A special kind of proficiency ride.

Do the ride in an airplane which is not your usual mount. It would be best if it was one with which you were totally unfamiliar. If you're a Piper man, make it a Cessna, If a high time Bonanza guy/gal, do it in a Cub. The objective of the ride is to check your basic flying and thought skills but also to see how well you can apply them in a new environment.

The format of the flight will be as if it is your first flight in the homebuilt and you're all alone. The instructor is just alone as an interested observer. You will be given the right climb and approach speeds, which you would also have if flying the homebuilt. Past that, the instructor won't say a word. It will be self-discovery all the way.

The flight will be conducted primarily in the pattern, since that's where most problems arise during homebuilt flights. You'll be asked to make a minimum of five take-off and landings to a full stop. During the flight, the instructor should keep a running tally of how well you do certain things like maintaining airspeed and attitude control, how smooth you are on the controls and how good your situational awareness is. At some point in the flight, he should simulate a couple of emergencies, including having to complete the flight with partial power, trim locked full in one direction or limited control movement on one or more axis.

Since your first flight in the homebuilt may encounter any of the above, it is the instructor's job to subject you to them to see how well you handle them. At the end of the flight both of you will know whether your proficiency and adaptability factor is high enough to handle your homebuilt.

First Flight Caveat

A note about doing the first test flights: In far too many cases a builder has the feeling that he built it, so he should make the first flight. In most of the cases, he's not the right one to do the first test flights because he not only hasn't flown enough recently to be current or proficient but he is also too close to the project to make rational, emotion-free decisions during the flight. In many cases, training will bring the pilot up to the level he can safely perform his own test flights. In many others it won't. In those cases, the builder should be willing to find the best qualified, most proficient pilot he can find who is familiar with the type. Even if he has to hire a pilot from the kit plane manufacturer and fly him in just for the first couple flights, it is a great investment. Most major kit manufacturers have such pilots who can also check out the owner.

In the case of the really high performance birds like the Glasair III, Lancair IV, Questair Venture and few others, you can't get insurance coverage without going through a formalized flight training program conducted by a company which the insurance company has blessed.

The incredibly wide field of homebuilt aircraft is populated by some of the best, most efficient designs ever to take to the air. It also has its fair share of rogues that take a special hand and spirit to fly. Homebuilt aircraft, however, offer the pilot so many different mechanical personalities, so many different forms of utility and recreation that they can't be ignored. They are here. They are growing and they are exciting. However, before jumping in with both feet and your checkbook. Get a little training.

Any pilot can fly any airplane. There is no magic or super human skill involved. Unless, of course you consider training to be magic. And maybe it is magic since it lets us do things we never thought possible. It lets us expand past our own envelops to become more than we once were.

We were right the first time. On that basis, training absolutely is magic.

A lot of us CFI's lie to ourselves. Or maybe we believe our own press. We think that because we have that piece of paper in our pocket we know what we're doing and, even if we don't, we think if we talk fast enough our students won't notice what we lack.

That's wrong. When it comes to instructing people for, or in, homebuilt aircraft, that's seriously wrong. We may be able to bluff our way through a C-182 check-out when we spend all our time in a C-152. But that won't work in a Glasair , or a Pitts Special or a Kit Fox. If we don't know that airplane fairly well, we could wind up biting ourselves and/or our student in the butt.

Many homebuilt airplanes are unforgiving of mistakes and this is no place to let our ego do the talking.

CFI homebuilt commandant number one says, "Thou shalt not do, nor say, what thou dost not knoweth to be fact." In other words, no B.S. allowed. If you don't know the airplane in question well, don't act as if you do.

Also, we shouldn't limit the check-out to three bounce and goes and call it quits. This is true with any airplane, but we'll apply it to homebuilts: We have to train the pilot to fly the entire envelope, not just the middle of it. This means flying off narrow, short runways, crosswinds and handling screwed up landings. If we don't do all of those, it is axiomatic that as soon as we turn him or her loose, the student's first solo landing is going to be on a narrow, short runway in a gusty crosswind.

If using an equivalent airplane, rather than giving dual in the real thing, we have to constantly reinterate that "...your airplane won't act like this at this point, it will..." We must always talk to the airplane to be flown.

A note about giving dual in the homebuilt: It's perfectly legal because we're just charging for our services, but when is it a good idea and when isn't it? It's a bad idea when the airplane has only a few hours on it because you'd have to be listed as "essential crew" to be legal and you'd have to be enormously experienced to be safe. Many homebuilts don't give us the margin of error Spam Cans do. We don't have has much time to let them screw up, try to recover it and still give ourselves enough time to save it. You wouldn't believe how fast a sink rate can build until you let a student get something like a Glasair/Lancair/Questair/etc. slow with only a little power in it. The same thing applies to something as basically benign as a Pietenpol for entirely different reasons. We can't depend on our superb skill to pull it out every time. Sometimes it won't.

Also, remember, homebuilt means just that...built at home. You have no way of knowing how well that airplane is screwed together, which is an excellent reason to pass on it until it at least has the hours restriction flown off. In some FSDO's you won't have the option anyway since they often won't let another person in the airplane during the test period. Just remember: Being a test pilot while giving dual instruction is a really lousy idea.

There are a lot of opportunities out there for specialized instruction in the homebuilt and sport arena, but we should jump into it only when we actually know what we're doing. In the right situation, it can be some of the most fun, self-satisfying instructing we'll ever do.