Classic

Trainers: Save Money and Be a Better Pilot |

|

PAGE TWO

Okay, now what about the airplanes? Which ones make the most sense and what are their pros and cons?

|

|

| Both the Cub and the Champ will require flying something more modern to get the instrument, and probably night, requirements. | It's not unusual to see later Champs equipped for both night and instrument work. |

The two most popular classic trainers were the 65 hp J-3 Cub and 7AC (or 7EC, 85 hp) Aeronca Champ. Both airplanes have their devotees (read that as border-line fanatics) and both have their strong and weak points.

The J-3 Cub is the standard by which just about every airplane, trainer and otherwise is measured. It’s cute, it’s relatively easy to fly and costs next to nothing to operate. You’d be hard pressed to burn over 4 gph in it. However, it is not a cheap airplane to buy. The very things that make it THE classic airplane have made it wildly popular which has driven the prices through the roof. Expect to pay $20,000 just to get into the game with a decent airplane. If you want a cream puff, change that first digit to a three.

The Cub, however, is a gentle, forgiving airplane that will teach you how to fly in ways a C-152 never thought about. And this is true of every classic trainer: You will come out of them a better pilot than in any modern nosedragger. Your coordination will be much better, as will your attention to nose attitude control. You’ll have a much better “feel” for what the airplane is doing because the airplane telegraphs what it’s doing. Simply learning on a tailwheel will raise your visual acuity several hundred percent. Because a tailwheel bird won’t tolerate sloppy touchdowns, you become very critical about the airplane’s attitude on touchdown, something C-152s or Cherokees could care less about. The single biggest advantage to learning in one of these old birds is that for the rest of your flying career, you’ll be a better pilot for it.

The post-war Champ was designed around all of the Cub’s short

comings. It is roomier, you fly from the front seat and the visibility

over the nose is outstanding (for a taildragger). It has about the

same runway manners although it touches down at a much higher speed

than a Cub (maybe as high as 40-45 mph, golly!). It’s heavier

which means it handles crosswinds a little easier and its higher cruise

speed (90 mph plus) makes it a little more useful for cross countries.

If, however, they ever decide to pick a poster child for the Adverse

Yaw Society, the Champ (and it’s cousin the Chief) will be it.

They have lots of adverse yaw, so your feet either get busy or every

flight will polish the bottom of your pants. This, by the way, is a

plus, not a minus. They make you work to keep the ball in the middle.

The Champ will generally cost 2/3rds to 3/4ths of what a similar Cub

would cost.

|

|

| The 120/140 and Luscombe are basically all metal and can weather the elements better. | The Luscome requires a better instructor but will make you a better pilot |

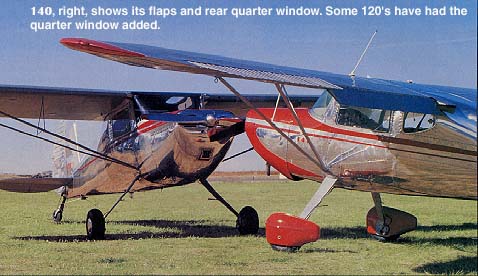

Joining the Champ and Cub and completing the triad of popular postwar trainers was the Cessna 120/140. Essentially, taildragger 150s (actually the 150 is a nosedragger 140), the airplanes offer much more modern feeling, side by side accommodations, control wheels (some consider that a negative), toe brakes and cross country speeds in the 105-115 mph range (at 5+ gph). Their spring gear makes them extremely forgiving on the runway and their all aluminum structure with fabric wings (the 140A has the single-strut, all-aluminum wing of the 150) makes them much better candidates to sit out tied down than the Cub and Champ which are fabric covered with easily-rusted steel structured fuselages. 120/140s run in the $12-$25,000 range and are extremely popular because they combine classic looks with relatively modern utility.

There are at least a half dozen other tailwheel classics that could

fit the trainer mold but the one which is most numerous is the Luscombe

8A (also E or F). The Luscombe is basically a more sprightly 120/140

Cessna with a more rigid gear and stick controls. However, finding

an instructor who is comfortable enough in the airplane to teach you

may be a real chore. The Luscombe is a very direct airplane on the

runway, meaning it does what you tell it to do. If you ask it to do

something stupid it will do just that and the instructor has to give

you time to correct your own mistake and still give himself time to

save it. Compared to all the rest of those mentioned, the Luscombe

gives the instructor less time so he has to be more familiar with the

airplane. Learn to fly a Luscombe with the right instructor, however,

and you’re going to come out a terrific pilot. The Luscombe is

also all-aluminum (with rag wings on many) so, it too can sit out with

less damage done by the elements.

|

|

The TriPacer is a HUGE bang for the buck |

The earlier straight-tail 172s, like this

'56 model, perform like new ones. |

Don’t want the challenge of a tailwheel? Then, look at the 1950’s crop of early nosewheel airplanes. The Piper Tri-Pacer, possibly the best value in the four-place field at $15-$25,000, makes a good trainer as well as cross country airplane (125 mph w/150 hp). Yes, it comes down quickly power-off, but that’s absolutely not a problem. Just a characteristic.

Also, don’t forget the C-172 came out in 1956 and the C-150 in 1959. Those early “square tail” Cessnas are gaining in popularity because their performance is almost identical to the modern airplanes at a fraction of the cost. Just make sure you’re getting a good airplane with a good engine or you may find you’ve just bought a high-wing money sucker.

There’s one other advantage to buying a classic to learn to fly in: It’s much more fun flying something with character. Also, when you’ve earned your PPL in your own airplane, there isn’t that period of “...I wonder if the a rental airplane is available.” You just saunter out to the aerodrome and strap on the airplane you know and understand and start living the life of the private pilot. BD

Want another

view point on flight training? Return to ARTICLES

If

you want to see how these airplanes fly go to PILOT

REPORTS