Baby Bipes:

One Wing is Never Enough

How about a canard biplane! Yeah, that's the ticket! New meets old.

What a great idea!

Oh, it's been done already? Oh, yeah, Orville and Wilbur. I forgot about

them.

Biplanes have been with us since day one and, in fact, were the first,

and favored type of homebuilt even before the Wright boys wandered on

the scene. It was shortly after graduating out of box kites that guys

like Lillenthal and Chanute began building biplanes and gliding down

every piece of sloping topography they could find. In fact, it may have

been the light, but rigid box-kite that gave them their inspiration in

the first place.

They needed light, extremely strong and easy-to-build structures. The

biplane was it. A century later, the biplane is STILL it. The stick and

wire structure is hard to beat when it comes to simplicity, reliability

and ease of construction.

At the beginning, there was no romance attached to a biplane. After

all, that's what all airplane's were. It was the up-start monoplanes

that were in the minority. Today, however, looking back on a century

of biplanes, it's impossible to miss the romance and satisfaction that's

attached to a wind-in-the-wires biplane.

Many don't realize that the homebuilt aircraft industry was alive and

thriving before WWI and a lot of the designs were biplanes. Then, in

the '20's, magazines loved to fill their pages with tempting plans and

pictures of baby bipes like the Lincoln Sport.

Leap over the war and homebuilding is reborn yet again, this time under

the marquee of the EAA. And the biplane is still there. This year, the

EAA will celebrate 45 years as an organization and the biplane, which

looked like it might be sliding off to the edges of 1990's sport aviation,

is coming on stronger than ever. Now we're seeing things like composite

sorta-Staggerwings and Curtis's latest, the Macho Stinker.

The biplane soldiers on.

In celebration of a century of bipes, we thought we'd do a round-up

of the more popular types as well as those golden oldies which are as

good now as they were then.

Golden Oldies

During the 1950's and early 1960's the goal was to get in the air as

economically as possible. The primary construction component was a

liberal amount of builder-supplied elbow grease. Kits didn't exist

and no one gave serious thought to having someone else build even a

small component of their airplane for them. The biplanes which came

out of that era reflected all of those concerns. They were simple,

straight forward machines designed specifically to be constructed by

the average handyman on a budget in his garage. And that's where the

majority of them came from.

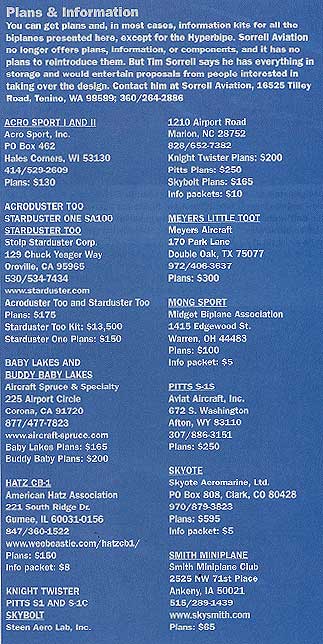

Knight Twister Knight Twister

Vernon Payne's inspired design actually pre-staged all other homebuilt

biplanes and, when it was introduced in 1929, was radical in the extreme.

It's tiny 55 sq. ft, finely tapered wing (15' span) scared a lot of

pilots. Payne stayed with the design, continually updating it until

his death just a few years ago. The larger wing airplanes (75 sq. ft.)

known as the Imperials are one of the sexiest airplanes ever designed.

Structurally, Payne's original design is an engineering tour d' force,

in its approach to lightness. The fuselage is a traditional, although

light, tubing structure but the wings and tail surfaces are super lightweight,

plywood covered, wood structures using balsa wood to fill in the gaps.

The airplane has suffered from a lot of bad press that appears to be

the result of early-day Cub pilots trying to fly what was essentially

a high performance airplane without proper training. The quintessential

1950's homebuilt was Tony Sablar's KT-85. Tony put 500 hours on the

airplane and had nothing but 120 and 140 time before flying it.

Mong Mong

Ralph Mong was, and is, a compact person and his airplane shows it. With

tiny wings and a narrow fuselage, it isn't made for the gravitationally

challenged. It is, however, one of the least expensive biplanes that

can be built, if only because it uses no flying wires. Mong chose to

use a single lift strut rather than the traditional cross of wires

to complete the structural truss of the wings. There is nothing in

the airplane that can't be built by the average builder with a bench

grinder and a welding torch. The airplane is happiest with a C-90 although

some were built with 65 hp. The Mong is fairly typical of the 1950's

short wing biplanes in that it assumes the general flight characteristics

of a clod of dirt, when power-off, but other than that, presents no

particular challenges to the modern day, well-trained tailwheel pilot.

Smith Miniplane (see

airbum.com pirep) Smith Miniplane (see

airbum.com pirep)

When Frank Smith's Miniplane, N90P, appeared on the cover of Popular

Mechanics in the late 1950's, sport aviation got an incredible shot

in the arm. That coverage alone may be why the Miniplane was the most

popular biplane of it's day. That and the fact it is a dead-simple,

easy to build and fly airplane. As originally designed, the airplane

had a rigid gear which made it prone to skip and bounce on landing.

A lot of builders changed that to a coil-spring gear. It's wings are

among the simplest of the type to build and small enough to fit in

any workshop. As with all airplanes of its type, it flies best when

light, so pilots who install 150 hp engines give away some of its basic

pasture goodness in search of performance. The airplane settles quickly

when the power is off and is quicker than many taildraggers on the

pavement. The old "...get some time in a Luscombe..." axiom

applies here.

Meyers Little Toot Meyers Little Toot

When biplanes were a major part of each fly-in, the Meyers Little Toot

was considered the Cadillac of the breed. Bigger, smoother, professionally

engineered, it offered the choice of either a tubing fuselage or one

with an aluminum tail-cone aft of the pilot. Being bigger, and therefore,

heavier, the airplane didn't perform well on the 85 hp Continentals

which was considered standard-issue for sport planes. In fact, the

airplane was, and is, quiet commonly seen with engines as big as 180

stuffed in it. Of all the older biplanes, the Toot had the best visibility

and best ground handling manners. It was a favorite for pilots wanting

to paint their airplane up in ersatz military markings because of its

hawk-like appearance.

Pitts Special (see

airbum.com pirep) Pitts Special (see

airbum.com pirep)

Although first designed in 1945, plans for the Pitts weren't commonly

available until 1960 when it was offered as the S-1C. The model designations

denote different wing configurations, the C (which originally stood

for Continental) had the relatively flat-bottomed M-6 airfoil with

two ailerons on the bottom wing, the S-1D had the same wings with four

ailerons and the S-1S, the most familiar competition model, has symmetrical

wings and four ailerons. The S-1C's have had engines as small as 85

hp and as large as hopped up 200's. In any configuration, all Pitts

are a delight to fly and not as demanding as their reputation would

portray. They are, however, not airplanes to be flown without adequate

check-out and preparation. Some dual in a two-place Pitts is worth

any amount of money. The Pitts has a one-piece top wing with the swept-back

spars spliced inside a plywood center section. The fuselage is trapezoidal

in cross section, rather than square, so the top and bottom trusses

are usually built first, rather than the sides. The cockpits get noticeably

longer in the later Cs and the "D" and

"S" models. The Pitts is the standard by which all other biplanes

are judged, not only in aerobatic capabilities, but in overall handling

and runway manners, as well. Just about all biplanes are easier on the

runway, none are as capable in the air.

Starduster One (see

airbum.com pirep) Starduster One (see

airbum.com pirep)

Lou Stolp's little airplane was, and is, one of the prettiest biplanes

ever designed. It's elliptical trailing edges are the result of changing

the airfoil at the rear, rather than having different ribs at each

station, so it's not as complicated as it looks. Also, the wing uses

a tubing truss for drag/anti-drag loads, rather than wires, which keeps

the cost down and eases construction. The airplane is just enough larger

than a Pitts that it is more sedate and possibly better suited to someone

who isn't up to handling the frenetic personality of the Pitts. It

might also be a better choice for those who are extremely long of leg.

GO TO PAGE

TWO

To

read pilot reports on many of the aircraft above

go to PILOT REPORTS.

|