There are a lot of goals in life that, when attained, open a huge number of doors. Taking your first step was one. Walking across the stage to get your diploma, another. Seeing your first born, still pink and all potential with every experience ahead of it, was a biggie. In many ways, that's exactly how most of us were (or will be) when handed our pilots license. We've worked, attained a goal and now all the experiences are in front of us. Now what?

A newly minted pilots license is like an unrestricted airline ticket with destinations limited only by our imagination. We have so many trips we've wanted to take, so many experiences we've wanted to share with friends and family. Now, the government has said we can do all those things. The all-seeing, all-knowing FAA has given us a piece of paper that says we are a pilot.

As new pilots most of us do one of two things almost immediately, both of which can lead to the same potential problem. If we learned in a C-172, we immediately call all our friends and family asking them to go flying with us. Or, if we learned in a C-152, we get checked out in a C-172 (2-3 hours), then start looking for people to load into the airplane. Then, we start planning that trip to California/Nantucket/Miami or Peoria we've always wanted to take. In other words, one of our very first moves as a super-green pilot is to load an airplane to the gills and take it someplace far outside our local area.

One of the frustrating aspects of teaching folks to fly is that the process is limited by time and money. It starts with the student at zero hours, zero experience and moves, as quickly as the instructor and student can possibly make it move, to a pilot candidate, with around 60 hours and limited experience, who can satisfy a one-flight test with an examiner. What frustrates most instructors is that so many of those hours are spent teaching skills, that while important, don't necessarily prepare the student for the changes he is going to see in his airplane in real world situations. As a normal rule, a new pilot is better prepared to deal with aviation's regulatory and navigational environments than they are with the stick and rudder aspects of the ever changing operational environments they will soon be experiencing.

One of the experience-factors instructors almost never get to exposure their students to is the way an airplane can change personalities, given different loads and operating conditions. Fortunately, most aircraft likely to be flown by a new student (172, 182, etc.), are forgiving and will let him safely fumble through those first experiences with density altitudes, sloped runways and so many other unpredictable factors. Too often, however, a new pilot gets himself into a situation where a number of factors stack-up and the resulting personality change in the aircraft catches him or her unawares and an accident is in the making.

Often a pilot gets himself into this kind of trouble as part of that first ambitious cross country. The one that takes him well outside the geography which he knows from his student days.

Student

cross countries don't necessarily prepare a student for the real

world because they are invariably selected by the instructor to

make it easy on both the student and the instructor. We don't

send a flatland student out over the mountains and we don't allow

them to fly trips that are likely to give them navigational heart

burn. We do this because the student needs a challenge he can

handle. The trips are supposed to teach the student, not scare

him. Besides, instructors worry about cross country students every

second they're gone, so, we're not fooling anyone: we want to

make it easy on ourselves, as well. Unfortunately, in so doing,

the majority of students get their licenses never having experienced

situations that may cause their airplane to change personality.

Student

cross countries don't necessarily prepare a student for the real

world because they are invariably selected by the instructor to

make it easy on both the student and the instructor. We don't

send a flatland student out over the mountains and we don't allow

them to fly trips that are likely to give them navigational heart

burn. We do this because the student needs a challenge he can

handle. The trips are supposed to teach the student, not scare

him. Besides, instructors worry about cross country students every

second they're gone, so, we're not fooling anyone: we want to

make it easy on ourselves, as well. Unfortunately, in so doing,

the majority of students get their licenses never having experienced

situations that may cause their airplane to change personality.

The major factors that cause aircraft personality changes fall into two categories. The first we'll call "environmental" because they involve factors outside the airplane itself, like density altitude, runway characteristics, etc. The second category are those things within the aircraft itself that cause changes which the student may not have experienced during training.

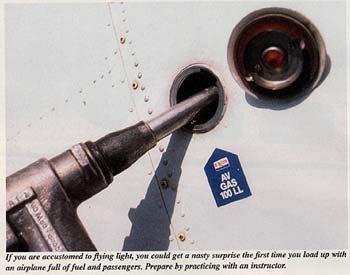

Of all the aircraft changes that are mostly likely to catch a student unawares, flying at full gross weight for the first time is certainly number one. It is seldom, if ever, that a student training in a C-172, or some other four place aircraft, experiences the surprising decrease in performance which results from simply putting two bodies in the back seat. Also, in many western training environments, a trainer is seldom flown with more than 3/4 tanks to keep the weight down. So, the student gets his license having always seen the airplane in light weight operating scenarios.

There is an interesting rule of thumb which came out of a Cessna POH, which says that increasing an airplane's weight 10% increases its takeoff roll 20%. In other words, for each 170 pounder put in the back seat, you can expect approximately a 20% increase in runway used. Two people and the increase is approximately 40%. That's a bunch!

All runway charts in POH's are predicated on full gross weight, so we're not talking about lengths beyond those in the POH. What we're talking about is an airplane that is suddenly going to take 40% more runway than the student is used to seeing. This type of change can be critical because all pilots, new ones or otherwise, are creatures of habit. Most of the takeoffs they've made in this particular airplane have taken about the same amount of runway and time. They've come to expect the airplane to fly after waiting a certain number of seconds. Anything which increases that period of time significantly puts them in new territory and they are likely to react exactly the way they shouldn't. They'll be thinking, "Surely the airplane should be ready to fly by now," and they'll try to force it into the air. If there's plenty of runway, they'll eventually stagger into the air and make it. However, if other factors further aggravate the weight-induced change in personality, they may not.

Assuming

they get the airplane off the ground safely, the pilot will then

be flying an airplane that really doesn't want to climb. At least

not the way they are used to. They'll be tempted to ignore best-rate-of-climb

speed and pull the nose up a little more, which further degrades

climb performance. In most aircraft, adding two people cuts the

climb performance by 30-40%, sometimes more. The first time a

new pilot sags into the air in this kind of situation, he'll notice

the trees suddenly look a lot taller.

Assuming

they get the airplane off the ground safely, the pilot will then

be flying an airplane that really doesn't want to climb. At least

not the way they are used to. They'll be tempted to ignore best-rate-of-climb

speed and pull the nose up a little more, which further degrades

climb performance. In most aircraft, adding two people cuts the

climb performance by 30-40%, sometimes more. The first time a

new pilot sags into the air in this kind of situation, he'll notice

the trees suddenly look a lot taller.

Adding weight to an airplane also changes the way an airplane "feels" because additional weight almost always drives the center of gravity back. As the CG approaches the rearward limits of the airplane's envelope, the airplane gets more sensitive in pitch and the pilot may get a little spooked, just because the airplane doesn't feel the way it used to.

If you're that brand new pilot take heart. There's a simple way to handle these kinds of problems; book some dual time and make some gross weight flights with an instructor before attempting them solo. This need not be done prior to licensing, but it certainly should be done before loading the airplane up and taking off for far horizons.

Another loss-of-performance learning experience may come the first time a new pilot rents an airplane from an operator other than his flight school. This introduces the sometimes significant differences between seemingly identical airplanes which are part of different operations. For one thing, although all 172s, for instance, are created equal, they certainly don't stay that way. Age and maintenance levels vary from rental fleet to rental fleet and these all take their toll on aircraft performance. As an airplane ages, it gets bent subtly out of shape and loses performance. On top of that, the engine is aging and what used to be a 160 hp engine, may be only cranking out 145 hp or so.

And then there's the propeller. All propellers are not created equal because they weren't meant to be equal. Each airplane/engine/prop combination is certified with a specific range of propeller pitches allowed and the performance difference from one end of the range to the other can be really eye opening. If you've been flying a 172 with a climb prop that would turn up 2400 rpm static and you then find yourself in a rental with a cruise prop that only delivers 2100 rpm static, you're going to think the airplane will never get off the ground. If enough other environmental factors are working against it that may be the case and it might not get off.

"Environmental factors" which can change an airplane's personality for the worse include just about everything about a flight that's not hardware oriented. Factors like density altitude, runway length, slope and surface are all lurking out there just waiting to surprise a new pilot.

The density altitude thing is often the most mis-understood or, at the least, is the one in which students (flatland students anyway) have the least experience. Something as seemingly benign as getting your license in December and taking your first, gross weight cross country in July has its density ramifications. In that situation, your 1,500 ft. MSL runway that had a density altitude of around 300 feet in December is suddenly up around 4,000 feet in July. The difference in performance is shocking.

What will come as even more of a shock is your first enroute takeoff from an airport that's at 3,500 feet MSL, which isn't even considered high by western standards. The density altitude there will be around 6,000 feet and your trusty Lycoming/Continental will be hard pressed to put out 70%- 75% power and probably not even that. Between the decreased power and the decreased efficiency of the wing, runway lengths all begin to look ridiculously short.

POH rules of thumb for this situation say an increase in altitude of 10% means a 10% increase in takeoff roll. Raise the temperature 10° C (18°F) and you can tack on another 10%.

A slight slope, about 1.5°, which is just enough that you can tell the airplane is working up hill will add another 10%.

So, let's say you're carrying two extra bodies, and we apply the rule of thumb while being conservative; that's a 30% increase in ground roll over what you're used to seeing, assuming the two passengers increased the weight by 20 percent. Then, assume it's late summer and a solid 20° F hotter than you're used to, there's another 20 percent increase in runway needed. Now we've increased the takeoff length half again over what you're used to seeing. So far, this isn't even remotely dangerous as long as you don't try to rush it off the ground.

Now let's say there's a slight slope, about 1.5° which is just enough you can tell it's there. Going up hill will cost you around 10% more runway. So you turn around and go down hill, but that puts a leisurely little 5 knot wind on your tail (10% of the takeoff speed). This will increase the ground roll a solid 20%, but the downhill slope will help shorten that. How much, we're not sure. Okay, now we're all confused.

See what's happening here? There are about a dozen things working on the airplane that are going to change the amount of runway it needs to get off the ground. In reality, none of these would make the average operation marginal as long as the pilot uses his head and doesn't force it off the ground prematurely. However, to let an airplane run until it's ready to fly in a high density altitude or weird runway situation without yielding to temptation and forcing it off takes a lot of self control. Unfortunately, self control is based on experience, both of which may be in short supply in a newly licensed pilot.

Much worse, a newly licensed pilot may not even be aware of what's happening because none of the factors affecting the change in the airplane's performance or handling have been explained to him or her. And then think about the compounding effect of a combination like high density altitude AND gross weight AND a cruise prop. Here we have an airplane that doesn't remotely resemble the airplane the student trained in.

We haven't even mentioned changes in the way an airplane lands because of the aforementioned factors. This is because most of the changes, while significant on landing, are not likely to get a student into serious trouble. Yes, the airplane lands at a higher ground speed when the density altitude is up and yes, a heavy airplane stalls at a higher speed than a light one and it takes more runway to stop. These differences, however, only become factors if the student is trying to put the airplane into a runway that would be considered short for the situation at hand. Hopeful, a new student won't be venturing out into the bush or challenging tiny runways until he or she has more experience.

So, what's the cure for lack of experience in these kinds of situations? Training! And it won't take much. The ingredients are simple. First get a willing instructor and two fearless friends. Then top the tanks and make sure you have loaded your trusty steed right up to gross. Then all you need is an hour of bashing around on every kind of runway you can find, and you'll be as good as you're going to get. The name of this particular game is staying ahead of an airplane's changing personality by learning it's quirks and how it changes. It'll be an hour well invested.