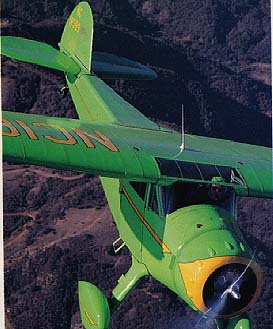

Classic! If you want to get literal about it, the word denotes something which has stood the test of time and become something which is elevated above the ordinary. This applies to everything from the '57 Chevy to Marlyn Monroe. It also aptly describes the group of airplanes produced in the decade following World War Twice. These are airplanes that include a wide, almost dizzying, variety of types, sizes and appearance but they almost all have one foot in a historical time long gone while having the other one firmly rooted in the utility of a modern airplane. It is one of the few places where you can literally have your aeronautical cake and eat it too.

Classics span the gap from the much loved Piper cub to the much-desired D-17G Staggerwing Beech, from the Ercoupe to the 35 Bonanza. We're going to focus our attention on those airplanes were designed and built for the postwar market, as some of the airplanes such as the Staggerwing, really do belong to another time and were produced in small numbers. Those traditional classics, the 120/140, Cubs, Swifts and a bunch of others that were part of the 35,000 airplane flood of 1946/47 were produced in huge numbers and today represent a total pool numbering well up in the thousands. This is another way of saying plenty are available, many of them at a decent dollar.

Almost as quickly

as the factories frantically geared up to build huge numbers of

airplanes for returning G-I's, they began hunkering down into

survival mode when it was realized that the much heralded boom

was actually a bust. By 1948, one of the more interesting decades

in aviation began as factories began searching for new product

designs the market might buy. Piper took their spare parts inventory

and built the Vagabond, which mutated into the Clipper, the Pacer

and finally the Tri-Pacer. Cessna worked on improving their 170,

adding metal wings, then big flaps and, finally, in 1956 the nosewheel,

thereby giving us the airplane which still defines light aircraft

to this day, the 172.

Almost as quickly

as the factories frantically geared up to build huge numbers of

airplanes for returning G-I's, they began hunkering down into

survival mode when it was realized that the much heralded boom

was actually a bust. By 1948, one of the more interesting decades

in aviation began as factories began searching for new product

designs the market might buy. Piper took their spare parts inventory

and built the Vagabond, which mutated into the Clipper, the Pacer

and finally the Tri-Pacer. Cessna worked on improving their 170,

adding metal wings, then big flaps and, finally, in 1956 the nosewheel,

thereby giving us the airplane which still defines light aircraft

to this day, the 172.

So, when you say "classic airplane," you're covering a superwide group of flying machines. At the same time, there are some caveats of purchasing and operating which apply to all of them.

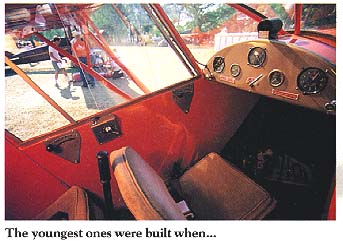

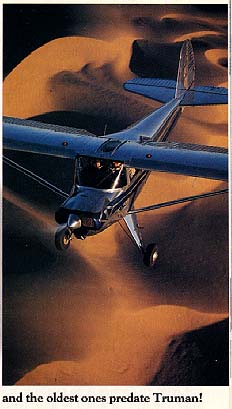

Certainly the one

unifying characteristic of the entire group, regardless of size

and complexity, is age. They are all old. The youngest was built

when Isenhower was in office and the oldest pre-date Truman. Most

of them are much older than the pilots flying them and the infirmities

of age have to be considered. If these were cars, they'd be relegated

to occasional parades and car shows, but we view most of them

as every day drivers to be utilized as if they were built yesterday.

But they weren't.

Certainly the one

unifying characteristic of the entire group, regardless of size

and complexity, is age. They are all old. The youngest was built

when Isenhower was in office and the oldest pre-date Truman. Most

of them are much older than the pilots flying them and the infirmities

of age have to be considered. If these were cars, they'd be relegated

to occasional parades and car shows, but we view most of them

as every day drivers to be utilized as if they were built yesterday.

But they weren't.

As a group, the classics represent both a hold over of steel tube construction and the first hard push into aluminum construction which had actually begun before the war with Don Luscombe being the most successful pioneer. The two materials will last forever, if properly cared for, but most weren't. Even the most expensive of the group, like the first Bonanzas, went through a period in the late '50's and 60's where they were pushed onto the back tie-down lines and forgotten as newer models took their place. Swifts, Stinsons, Taylorcrafts, Champs/Chiefs, and dozens of others were literally abandoned and, in so doing, were exposed to the elements for years. With the exception of the lucky few left out in the dry parts of the West, many of the airplanes suffered mightily during that period. The buyer of even a restored airplane has to remember it's not only a half century old, but at some point in its life probably sat out in the rain for a long time and this has to be part of the buying decision. With most of the classics, condition far outweighs the usual yard stick of flight time. The number of hours on an airframe is seldom a serious problem, as most of the airplanes were retired before they went much past 2,000 hours.

Condition on these

old airplanes centers first on those problems brought about by

the period during which they were derelicts. In other words, rust

and corrosion. Some of the classics, like the Luscombe, have closed

areas that have been collecting moisture for over 50 years. The

Luscombe, for one, has a mod that puts inspection panels in the

wings so the closed areas can be looked at. All others absolutely

have to inspected with a mirror and flashlight looking for that

tell tale whiteness that says corrosion is at work. Since most

of the airplanes are taildraggers, just imagine yourself as a

droplet of water and where you would run if dropped inside. The

problems on aluminum airplanes are usually on the bottom, front

of spar faces and stiffener interfaces with the skin. On steel

tubing structures, it's usually the clusters towards the back

of the fuselages, or in the case of the shortwing Pipers, in the

areas of the door frame and carry throughs where the framing forms

pockets that can hold water.

Condition on these

old airplanes centers first on those problems brought about by

the period during which they were derelicts. In other words, rust

and corrosion. Some of the classics, like the Luscombe, have closed

areas that have been collecting moisture for over 50 years. The

Luscombe, for one, has a mod that puts inspection panels in the

wings so the closed areas can be looked at. All others absolutely

have to inspected with a mirror and flashlight looking for that

tell tale whiteness that says corrosion is at work. Since most

of the airplanes are taildraggers, just imagine yourself as a

droplet of water and where you would run if dropped inside. The

problems on aluminum airplanes are usually on the bottom, front

of spar faces and stiffener interfaces with the skin. On steel

tubing structures, it's usually the clusters towards the back

of the fuselages, or in the case of the shortwing Pipers, in the

areas of the door frame and carry throughs where the framing forms

pockets that can hold water.

All other things being equal, the key to an old airplane's condition

is how much moisture it has seen in it's life time. Even an airplane

that's been hangared it's entire life, but the hangar was in sight

of the ocean, will be suspect. A faded flying machine that looks

like a dried out old cowboy boot from sitting out on a dirt strip

north of Tucson will be in much better basic condition.

Damage is another constant in many of the old airplanes. Most

are taildraggers so have suffered the vagaries of a public which,

for a period of time, had rapidly decreasing tailwheel proficiency.

Today, that trend has definitely reversed, but not before many

of the airplanes were ground looped or put over on their backs.

Careful inspection of landing gear attach points and gear boxes

is in order, along with inspections of the outer wing panels and

struts. Finding repaired damage is no reason to reject the airplane.

The only reason to reject it would be if the repairs were done

poorly.

The engines in vogue at the time range from the less commonly

seen Franklins of the Stinsons, to the E-185's of the early Bonanzas,

to the common-as-dirt 0-320's of the later Tri-Pacers. The good

news is that, for the most part, the engines are still relatively

easily maintained although parts availability is becoming tight

on the less common engines. What happens in every one of these

harder-to-maintain cases, however, is several shops begin specializing

in those engines, like the Franklins, so help is always to be

found. The more common engines, like virtually all of the early

Continentals and Lycomings, are still easy to maintain.

A minor support problem is finding a mechanic familiar with both

the engine and the airframe who can do more than simply twist

bolts. The older the airplane, the more important it is to have

a mechanic who knows the type and knows where to look for wear

points and possible problem areas.

On some of the airplanes, especially those like Cubs, which use

expander tube brakes, a hard decision between reality and originality

has to be made when rebuild time comes. The cost of parts for

expander tube brakes has gone up to the point that it's possible

to spend as much as $3000 on a complete rebuild. A Cleveland conversion

is less than a third that, but isn't original and usually puts

too much brake on the airplane.

Something which has to be faced sooner or later on those airplanes possessing electrical systems, like Swifts, Cessna 140's, etc., is that eventually they'll have to be rewired. Especially if they sat out for a long period of time. Most of the airplanes used wiring with cotton insulation or some other type that may be deteriorating. All of these airplanes should have a careful electrical once-over before launching off into the dark where seldom-used parts of the electrical system may have juice forced through them. A smoke-filled cockpit in the dark is no fun.

As far as flight characteristics go, almost every one of the classics

is a pussy cat, although, in some cases, they are a lethargic

pussy cat, as they are slightly under powered. This, however,

becomes a factor only in areas where density altitude is a way

of life. In general, everything they do will be slightly slower

than their modern counterparts. They roll slower with higher aileron

forces (the Stinsons and Swifts being real exceptions here as

they are slick, great feeling airplanes) and more adverse yaw,

don't climb quite as well, have less visibility because of seat/wing/windshield

arrangements. This is especially true of the 1940's airplanes,

while the 1950 birds almost completely close the gap on new airplanes.

The difference between a 1956 172 and a new Skyhawk, for instance,

is almost entirely a matter of cosmetics. It should be mentioned,

however, that many of the smaller classics, e.g. Luscombe, Taylorcraft,

etc., have long wings to get good performance on small engines.

This means they are lightly loaded and require a little more finesse

in gusty crosswinds.

And then there is the dreaded TAILWHEEL! Can it be mastered? Will

the airplane willfully ground loop the instant it is untied? Can

only super-beings fly airplanes so equipped? What a crock!

We forget that the nosedragger, taildragger controversy didn't

even exist until the 152/172/Tri-Pacers became prevalent enough

as trainers that a generation of pilots was born with dead feet.

Every pilot before them just took the taildragger for granted.

That's the way airplanes were, so that's the way they flew them.

Today, there are enough tailwheel

schools and instructors that getting training isn't that difficult.

Depending on the individual, figure about six hours average to

transition with another couple of hours of post-solo dual spent

working in nasty crosswinds as insurance. There is no magic to

the tailwheel. All it requires is some of the basic skills you

were supposed to develop in the first place and, once you've become

comfortable with the tailwheel, you'll discover an entire new

world open to you.

Today, there are enough tailwheel

schools and instructors that getting training isn't that difficult.

Depending on the individual, figure about six hours average to

transition with another couple of hours of post-solo dual spent

working in nasty crosswinds as insurance. There is no magic to

the tailwheel. All it requires is some of the basic skills you

were supposed to develop in the first place and, once you've become

comfortable with the tailwheel, you'll discover an entire new

world open to you.

Today, the 1945-1960 airplane population is a gigantic, untapped

reservoir of pure fun and utility. $10-20,000 buys a huge amount

of enjoyment, but don't go into it thinking you're buying an airplane

that was built yesterday. It wasn't, so you have to care for it

and treat it accordingly. Once you know its idiosyncrasies, you'll

get more fun for less money than anywhere else in aviation.

For more information on any given type of Classic,

call the Experimental Aircraft Association (920-426-4800) and

ask their information services for the address and phone number

of the Type Club which supports that particular airplane. The

EAA also has an article series which compares the different classics

which may be of some value to you. Enjoy.